Résumé:

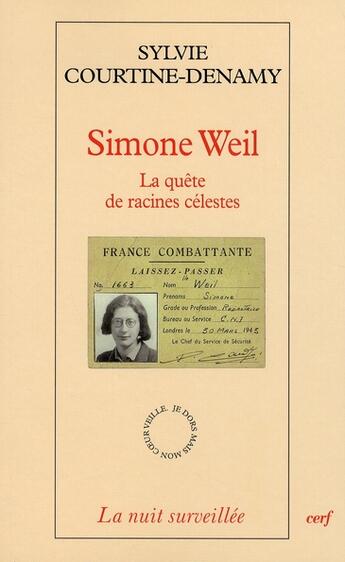

En 1943, Simone Weil, après avoir pris la route de l'exode vers Marseille, puis celle de l'exil vers New York, a finalement réussi à se faire rapatrier à Londres dans les services de la France libre pour partager le sort de ses compatriotes. Elle y rédige son " second grand oeuvre ", que sa mort... Voir plus

En 1943, Simone Weil, après avoir pris la route de l'exode vers Marseille, puis celle de l'exil vers New York, a finalement réussi à se faire rapatrier à Londres dans les services de la France libre pour partager le sort de ses compatriotes. Elle y rédige son " second grand oeuvre ", que sa mort l'empêcha d'achever, " L'Enracinement ". En vue de la réorganisation de la France après-guerre, la philosophe formule un certain nombre de propositions politiques pour remédier à la maladie dont souffrait son époque, le déracinement. Pour porter ce diagnostic, celle qui était trop bien née, voulut se déraciner, partager les humiliations de ceux que le hasard de la naissance avait moins favorisés qu'elle, se frotter au réel. Agrégée de philosophie, elle endura successivement dans sa chair la dure condition ouvrière, puis celle du monde agricole. S. Weil affirmait haut et clair n'avoir aucune racine dans la tradition juive -; " on n'hérite pas d'une religion " -; même si le régime de Vichy la renvoya à son ascendance. Pourquoi celle qui prétendait être née et avoir grandi dans " l'inspiration chrétienne ", le seul réel garant à ses yeux contre le désordre de l'époque, ne parvint-elle pas à franchir le seuil de l'Église, demeurant en attente, incapable pour sa part de prendre racine en ce monde ? Peut-être parce que " seule la lumière qui tombe continuellement du ciel fournit à un arbre l'énergie qui enfonce profondément dans la terre les puissantes racines. L'arbre est en vérité enraciné dans le ciel ". -- In 1943 Simone Weil, after making her way to Marseilles, then taking the route to exile in New York, finally succeeded in being repatriated to London and the 'France Libre' unit, where she wished to share the lot of her compatriots. There, she wrote her 'second great book' which her death prevented her from finishing, 'The Need for Roots'. Contemplating the reorganization of post-war France, the philosopher makes a number of political propositions to cure the sickness that afflicted her times, 'uprootedness'. In order to make her diagnostic, she who was too well-born had to free herself from her roots, share the humiliations of those that the hazard of birth had made poorer than her, rub shoulders with reality. Holder of a PhD, she endured the hard life of a labourer, then a farm worker. S. Weil declared loud and clear that she had no roots in Jewish tradition - 'you cannot inherit a religion' - even though the Vichy regime was aware of her ancestry. So why is it that she who was born and grew up in 'Christian inspiration' - the only real defence, to her mind, against the disorder of those times - could not cross the threshold of the Church, but remained 'waiting on God', incapable of taking root in this world? Perhaps because, as she wrote, 'only the light that falls continually from the sky can give a tree the energy to plunge its powerful roots into the soil. The tree is, in reality, rooted in the sky.'